Yutani Loop: Building an Agentic Malware PoC to Understand Tomorrow's Threats

Agentic malware is different. It decides what to do, not just how to do it. To understand these emerging threats, we built Yutani Loop — a...

This post is based on a talk by our resident researcher Candid Wüest at Black Hat Europe 2025.

Hardly a month goes by without a major discovery about how AI is being used by cybercriminals. If you take media reports at face value, you might believe we've already lost the fight against AI-powered threats — that AI malware dynamically adapts to every environment, discovers hidden sensitive data, and bypasses every security control in its path.

Spoiler alert: that's not reality. At least not yet. This post clarifies what we actually observe at the front lines and expands on themes from a previous blog post: The AI-Powered Malware Era: Hype or Reality?

A useful starting point is distinguishing between the two categories AI-generated malware and AI-powered malware.

While we see AI impacting other areas as well — for example, AI-assisted pentesting, phishing, and deepfake BEC scams — this article focuses specifically on AI-powered malware.

Reports of malware created with help from generative AI continue to increase. A notable case was the AsyncRAT dropper reported by HP Wolf Security in June 2024.

We cannot always verify if code comes from AI, but telltale signs exist — for example, the sample contained French-language comments, a common artifact of AI-generated code. Forum discussions also suggest the authors relied on AI.

Other examples include the FuncSec ransomware group, Rhadamanthys loader, NPM Kodane wallet stealer, Koske Linux crypto miner, and the Calina AI polymorphic crypter.

Attackers are experimenting with more advanced techniques. At Black Hat USA, Outflank presented research showing how a model trained on malware via reinforcement learning could generate new samples.

These samples bypassed Microsoft Defender in ~8% of cases. While low, the takeaway is simple: it works at least some of the time. But success drops quickly when trying to evade multiple tools.

Other researchers have shown how LLMs can obfuscate existing malware to bypass static detection — for instance, through string splitting or variable renaming.

However, these techniques rarely defeat behavioral detection. The novelty lies in automating known evasion methods, not inventing new ones.

In August 2025, Anthropic reported that several cybercriminals abused their models.

One attacker allegedly used Claude to breach 17 organizations, exfiltrate data, and issue ransom demands. The LLM helped plan the attack, choose what to steal, and determine ransom amounts — acting like a virtual senior operator rather than an autonomous system.

In November, a Chinese APT group reportedly automated 80–90% of their intrusion workflow using Claude to orchestrate open-source pentesting tools.

While Anthropic has improved guardrails, the case reinforces a critical point: guardrails cannot eliminate malicious use, especially for open-weight models that attackers can modify freely.

Separately, projects such as AIxCC, XBOW, and Horizon3 AI have shown how AI can fully automate initial penetration testing. Attackers can now scan and exploit large portions of the internet 24/7 — a capability that previously required significant expertise and effort.

AI has made malware development easier than ever — a trend some call "Vibe Hacking." But context matters: malware development was already accessible to non-experts thanks to toolkits, tutorials, and Malware-as-a-Service offerings. AI lowers the barrier further, but that barrier was already very low.

In theory, AI could increase the volume and speed of malware production. In practice, we don't see this happening. Data from AV-Test shows new malware volume holding steady at roughly 7 million samples per month.

While the profile of attackers may be changing, there's no evidence of an exponential surge in malware samples. More importantly, we have yet to see AI-generated malware introduce genuinely novel techniques that evade existing detection methods.

Industry data supports this view. At RSAC 2024, Vicente Diaz of VirusTotal reported analyzing 860,000 samples without finding evidence of sophisticated AI-generated malware. Similarly, Google's November AI threat report documented five AI malware cases but noted no new capabilities.

This points to a broader pattern: generative AI excels at reproducing techniques from APT reports, the MITRE ATT&CK framework, and research papers — but struggles to invent truly novel methods. As a result, modern security tools can still detect and block today's AI-generated malware, provided they are properly configured and maintained.

One area evolving quickly is the use of prompt injections to evade AI-based analysis. Researchers have demonstrated proof-of-concept malware that embeds prompt injections in its code, aiming to trick automated AI tools into misclassifying or ignoring malicious behavior.

While early samples failed to achieve meaningful evasion, other projects — such as Whisper — have successfully fooled specific AI-based analysis systems. The good news: no universal "one-prompt-for-all" injection has emerged that can bypass all analysis models.

AI-generated malware is real and growing, but it largely represents "more of the same" — just produced faster and at greater scale. It hasn't introduced radically new techniques. The main risk is that sheer volume could overwhelm defenders, making automation essential to keep pace.

The more advanced category is AI-powered malware — threats that embed a generative AI component or connect to one at runtime. Unlike AI-generated malware, these threats make dynamic decisions during execution.

In July 2025, CERT-UA reported on LameHug, the first pseudo-polymorphic infostealer observed in the wild using generative AI.

Delivered via email, LameHug contained hardcoded English-language prompts and queried Hugging Face's Qwen 2.5 model to generate commands on the fly. In theory, this should produce slightly different commands each execution (because generative AI is non-deterministic). In practice, because the developers set the temperature to 0.1 (to reduce hallucination), the generated commands were identical in 99% of cases, which meant that static signature detection still worked.

Technically, LameHug isn't truly polymorphic: the binary itself remains static, with a fixed hash. Only the executed commands vary. CERT-UA attributed the campaign to APT28, which Microsoft and OpenAI had already observed abusing generative AI for reconnaissance in 2024. The 283 hardcoded API keys have since been revoked.

PromptLock is a ransomware proof-of-concept created by NYU researchers and later discovered on VirusTotal by ESET in August 2025.

It uses OpenAI's GPT-oss-20b model via Ollama, allowing attackers to run the 13GB model locally or proxy requests to attacker-controlled infrastructure. This reduces the risk of provider takedowns — but downloading and running a 13GB model on a typical laptop is highly suspicious and likely to trigger alerts.

Like LameHug, PromptLock relies on hardcoded prompts for environment analysis, file discovery, and encryption. The LLM generates Lua code dynamically for cross-platform compatibility, but the prompts are extremely detailed — step-by-step instructions that essentially "hand-hold" the model. This reveals a key limitation: the malware isn't truly autonomous. The static prompts also make it easier to detect.

Similar concepts have been explored in proof-of-concept projects like BlackMamba, LLMorph III, and ChattyCaty. The underlying idea — polymorphic or metamorphic malware — is hardly new. Dark Avenger's Mutation Engine popularized it in the 1990s.

That it took over two and a half years after ChatGPT 3.5's release for the first AI-powered malware to appear in real attacks suggests the approach isn't yet compelling for most attackers.

Defenders shouldn't panic. Current AI-powered threats have significant weaknesses:

That said, the landscape may shift as local AI models become ubiquitous. Infostealers like QuiteVault (aka s1ngularity) already abuse locally installed AI command-line interfaces.

The next evolutionary step is agentic malware — threats that don't just use GenAI to generate code for predefined tasks, but autonomously decide *which* tasks to execute.

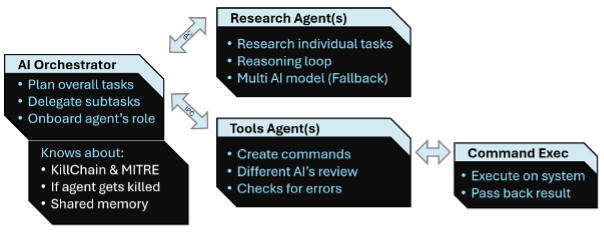

To study these risks, we developed Yutani Loop — a proof-of-concept agentic PowerShell swarm that separates planning from execution.

Architecture:

The agents communicate via IPC, spreading activity across multiple processes to complicate behavioral detection. This also enables basic learning — when a tool agent is terminated by security software, the swarm can adapt.

This isn't revolutionary; it's the logical next step. Similar ideas have been explored by: Unit42's theoretical agentic attack framework, CMU & Anthropic's INCALMO module for orchestrating agentic attacks, and AI Voodoo's agent research — to name a few.

Our experiments revealed several important insights:

|

What worked |

What didn't work |

|

Swarm architectures outperform single-agent designs. |

External dependencies quickly become chaotic. Agents frequently tried downloading third-party tools, creating dependency nightmares. |

|

Prompt precision is critical — vague prompts lead to cascading errors. |

Even at temperature 0.2, roughly 20% of generated code was non-functional (tested with Grok 4 and others). A second verification model helped only marginally. |

|

Scanning the environment for security tools and adapting to it. |

Stopping criteria are unreliable. Agents often "over-try," endlessly pursuing impossible goals like searching for a Bitcoin wallet that doesn't exist. |

We avoided using the Model Context Protocol (MCP) to keep the PoC lightweight, but as MCP servers grow in popularity, attackers could easily abuse linked tools for stealthier attacks.

The PoC could identify EDR products and devise strategies to bypass them based on published research. However, most documented techniques no longer worked — vendors had already patched the vulnerabilities. In one case, the agent tried to disable EDR via a vulnerable driver, but couldn't find one that wasn't already blacklisted. This shows that knowing the concept does not mean that it can be applied successfully.

When the PoC tried different persistence methods on each run (Registry Run keys, scheduled tasks, execution chain modifications), the frequent changes themselves triggered security alerts. To fix this, we advised the process to generate a new language prompt, specific for the first chosen method, and then store it (encrypted) in the process. This removed hard-coded language prompts from the sample, and ensured consistency in the chosen methods. Of course, we did not limit the sample to English; instead, we had it choose from common languages when generating the prompt.

Feeding enough behavioral data to an external agent introduces latency and exposure. If security tools terminate the malware, it can't report back or retry — a significant limitation for autonomous propagation. Analyzing EDR log files and alerts can help if they are accessible.

Looking ahead, attackers may exploit:

Do AI-generated and AI-powered threats spell the end of cyber protection? The short answer is No.

These threats are not undetectable — they're simply *not yet detected* in some cases. Behavior-based detection, with or without AI assistance, remains effective.

Attackers are scaling faster than ever. Defenders must match this pace with automation — likely AI-driven — to respond to alerts in time. The long-predicted AI-vs-AI battle in cybersecurity is no longer theoretical.

Organizations with unpatched systems, insecure remote access, or accumulated technical debt will be compromised by automated attacks. Best practices aren't optional anymore.

Soon, visibility and alerting alone won't suffice. By the time an analyst reads an AI-generated incident summary, the damage may be done.

What's needed is a careful balance: automatically containing threats using AI and SOAR, while avoiding unnecessary outages from cleverly crafted false positives.

Attribution is getting harder. Historically, analysts could group malware by coding style. As more attackers adopt "Vibe Hacking," those distinctions will blur. File hashes and filenames will become increasingly unreliable as self-modifying malware proliferates.

Very briefly: AI-powered malware is possible. It helps attackers move faster, scale operations, and evade static signatures — but it remains unreliable and unpredictable. At present, there are no significant benefits for attackers to rely on fully AI‑powered malware. Instead, we expect them to focus on automation frameworks and use lightweight malware payloads to execute the generated commands on the target.

Agentic malware is different. It decides what to do, not just how to do it. To understand these emerging threats, we built Yutani Loop — a...

Candid Wüest

Candid Wüest

AI-generated malware: what’s fact and what’s fiction? At this year’s Insomni’Hack conference in March (Lausanne), we’ll be diving into this topic....

xorlab team

xorlab team

The email lure is designed to convince recipients that they need to migrate their cryptocurrency wallet to a new one to improve security - often...

Candid Wüest

Candid Wüest