It's cyber week in Las Vegas: Impressions from Black Hat, BSidesLV, and DEF CON

First Impressions Overall, it was great fun participating in these conferences, meeting people, and listening to technical talks. The networking...

This post accompanies one of our talks at Black Hat Europe 2025. For broader context on AI-powered threats, see Agentic AI in Malware: Current Capabilities vs. Hype.

Most AI-powered malware today follows a simple pattern: hardcoded prompts query a language model, which returns commands to execute. The malware doesn't think — it follows a script, with AI filling in the blanks.

Agentic malware is different. It decides what to do, not just how to do it. To understand these emerging threats, we built Yutani Loop — a proof-of-concept agentic PowerShell swarm.

Agentic threats go beyond automation. They exhibit:

This isn't science fiction. The building blocks already exist. Yutani Loop demonstrates how they fit together.

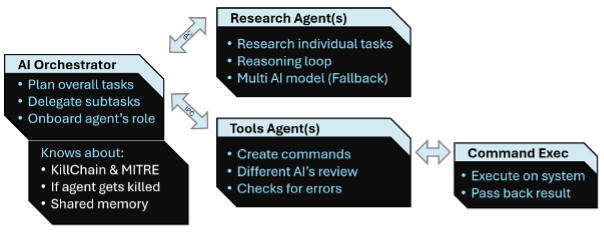

Yutani Loop separates planning from execution using a multi-agent architecture. Each agent has a distinct role:

The orchestrator agent is the brain of the operation. It receives the overall goal (e.g., "exfiltrate sensitive documents"), understands the attack kill chain and MITRE ATT&CK techniques via its system prompt, and creates a strategy. It breaks complex objectives into subtasks and delegates them.

The research agent receives subtasks from the orchestrator and identifies the best method to accomplish each one. It draws on knowledge of common techniques, tools, and procedures.

An optional quality-control layer. It validates outputs using a second AI model before execution, catching obvious errors or hallucinations.

The tool agent generates PowerShell commands based on the chosen method and executes them directly in memory. Results and error codes flow back to the orchestrator for follow-up or correction

The agents communicate via inter-process communication (IPC), spreading activity across multiple processes. This complicates behavioral detection — no single process exhibits the full attack pattern.

This architecture also enables basic learning. When a tool agent is terminated by security software, the swarm notices. The orchestrator can adapt: try a different technique, switch to a stealthier approach, or abort that subtask entirely.

Yutani Loop isn't unique — it's the logical next step, and others are exploring similar ideas: Unit42's theoretical agentic attack framework, CMU & Anthropic's INCALMO module for orchestrating agentic attacks, and AI Voodoo's agent research — to name a few.

Building and testing Yutani Loop revealed hard truths about what works — and what doesn't — in agentic malware.

Swarm architectures outperform single agents. Distributing tasks across specialized agents produces better results than one monolithic agent trying to do everything.

Prompt precision is critical. Vague prompts lead to cascading errors. The orchestrator's system prompt required careful tuning to produce reliable strategies.

Dynamic prompt generation beats hardcoding. Rather than embedding fixed prompts, having the agent generate and encrypt its own prompts (based on the target environment) improved consistency and reduced static signatures.

External dependencies create chaos. Agents frequently tried to download third-party tools to accomplish tasks, leading to dependency nightmares and broken workflows.

Code generation remains unreliable. Even at temperature 0.2, roughly 20% of generated PowerShell code was non-functional. We tested with Grok 4 and other models. A second verification model helped, but only marginally.

Stopping criteria are unreliable. Agents often "over-try," endlessly pursuing impossible goals — like searching for a Bitcoin wallet that doesn't exist on the target system.

We avoided using the Model Context Protocol (MCP) to keep the PoC lightweight, but as MCP servers grow in popularity, attackers could easily abuse linked tools for stealthier attacks.

The PoC could identify EDR products and devise strategies to bypass them based on published research. However, most documented techniques no longer worked — vendors had already patched the vulnerabilities. In one case, the agent tried to disable EDR via a vulnerable driver, but couldn't find one that wasn't already blacklisted. This shows that knowing the concept does not mean that it can be applied successfully.

When the PoC tried different persistence methods on each run (Registry Run keys, scheduled tasks, execution chain modifications), the frequent changes themselves triggered security alerts. To fix this, we advised the process to generate a new language prompt, specific for the first chosen method, and then store it (encrypted) in the process. This removed hard-coded language prompts from the sample, and ensured consistency in the chosen methods. Of course, we did not limit the sample to English; instead, we had it choose from common languages when generating the prompt.

Feeding enough behavioral data to an external agent introduces latency and exposure. If security tools terminate the malware, it can't report back or retry — a significant limitation for autonomous propagation. Analyzing EDR log files and alerts can help if they are accessible.

Yutani Loop demonstrates that agentic malware is buildable today. But it also reveals significant limitations that defenders can exploit:

Looking ahead, we see the risks to increase as:

Agentic malware isn't here in force yet. But the gap between proof-of-concept and real-world deployment is shrinking. Understanding these threats now — their capabilities *and* their limitations — gives defenders time to prepare.

First Impressions Overall, it was great fun participating in these conferences, meeting people, and listening to technical talks. The networking...

Candid Wüest

Candid Wüest

Earlier this month, OpenAI released its new Responses API, enabling developers to build AI agents with built-in functionality for web search, file...

Candid Wüest

Candid Wüest

AI-Generated Malware vs. AI-Powered Malware A useful starting point is distinguishing between the two categories AI-generated malware and AI-powered...

Candid Wüest

Candid Wüest